- Introduction

Illness often produces changes in appearance that extend beyond physical transformation and influence a person’s emotional and social life. When the face is affected, these changes may alter both self-perception and the way individuals are recognized within their communities. Eyebrow loss following chemotherapy or autoimmune conditions frequently becomes one of the most visible indicators of illness, and many survivors describe such changes as deeply unsettling for their sense of identity [1]. Because the face functions as a primary medium of emotional expression and social presence, even minor disruptions can carry significant cultural and symbolic meaning.

Research on facial perception highlights the importance of specific facial cues in human interaction. Eyebrows play a central role in recognition, expressivity, and assessments of health or vitality [2]. When these cues are diminished, individuals may experience a feeling of disconnection from their previous appearance, accompanied by uncertainty about how others interpret their visual presentation. This form of dissonance is not solely aesthetic; it influences the continuity of self and affects participation in everyday social interactions.

Sociological perspectives further illuminate the challenges associated with visible signs of illness. Changes in appearance can function as markers that inadvertently disclose a person’s medical history, potentially leading to a “spoiled identity” in which everyday interactions are shaped by assumptions, avoidance, or heightened attention from others [3]. For many survivors, the absence of eyebrows is not simply a cosmetic concern but an unwanted signal that communicates vulnerability or ongoing recovery. Restoring facial features, therefore, becomes closely linked to regaining autonomy, privacy, and a sense of familiarity with one’s own reflection.

In this context, cosmetic reconstruction can serve as a culturally meaningful form of emotional support. Naturalistic restorative methods help individuals restore expressive facial elements and reestablish visual continuity after illness [4]. This form of cosmetic art contributes not just to aesthetic enhancement but to emotional recovery, confidence, and reintegration into social life. The present study examines the cultural and emotional significance of such interventions, considering how aesthetic restoration can help individuals navigate post-illness identity and reclaim a coherent sense of self.

- Methods And Techniques.

The present study employs a qualitative cultural-analysis approach designed to examine the emotional and symbolic dimensions of appearance restoration after illness. Because the topic concerns identity, perception, and culturally embedded interpretations of the face, the analysis relies on conceptual frameworks rather than quantitative measurement. The methods used draw from cultural studies, sociology, and psychosocial research, with emphasis on interpretive techniques that illuminate the lived experiences of individuals undergoing post-illness recovery.

The study is grounded in three primary methodological components.

First, it incorporates findings from qualitative survivorship research that documents the emotional and social implications of appearance loss among diverse populations [1]. These accounts provide insight into how survivors describe the disruption of identity, the experience of involuntary visibility, and the challenges associated with social reintegration.

Second, the analysis draws on evolutionary and perceptual research concerning the cultural significance of facial features [2]. This body of work helps clarify why certain elements of the face, including the eyebrows, play a central role in recognition, expressivity, and assessments of wellbeing. These insights support the interpretation that restoring facial cues contributes not only to appearance but to psychological stability and social ease.

Third, sociological theory concerning stigma and the management of socially visible differences provides a framework for understanding how appearance changes after illness may influence public identity [3]. This perspective supports the idea that cosmetic restoration serves as a means of reclaiming control over personal presentation and reducing the unintended disclosure of medical history.

In addition to these theoretical sources, the study includes illustrative examples drawn from contemporary restorative cosmetic practice. These examples are used not to evaluate technique but to demonstrate how aesthetic methods can participate in emotional healing and identity reconstruction [4]. The examples were selected based on their relevance to themes identified in the literature, including identity continuity, social participation, and cultural expectations regarding normalcy.

The techniques employed in the analysis are interpretive and comparative, focusing on identifying cultural patterns and emotional themes rather than establishing causal relationships. The discussion synthesizes insights across disciplines to show how cosmetic art occupies a meaningful intersection between appearance, cultural norms, and emotional recovery.

- Results and discussion.

THE FACE AS A CULTURAL SYMBOL.

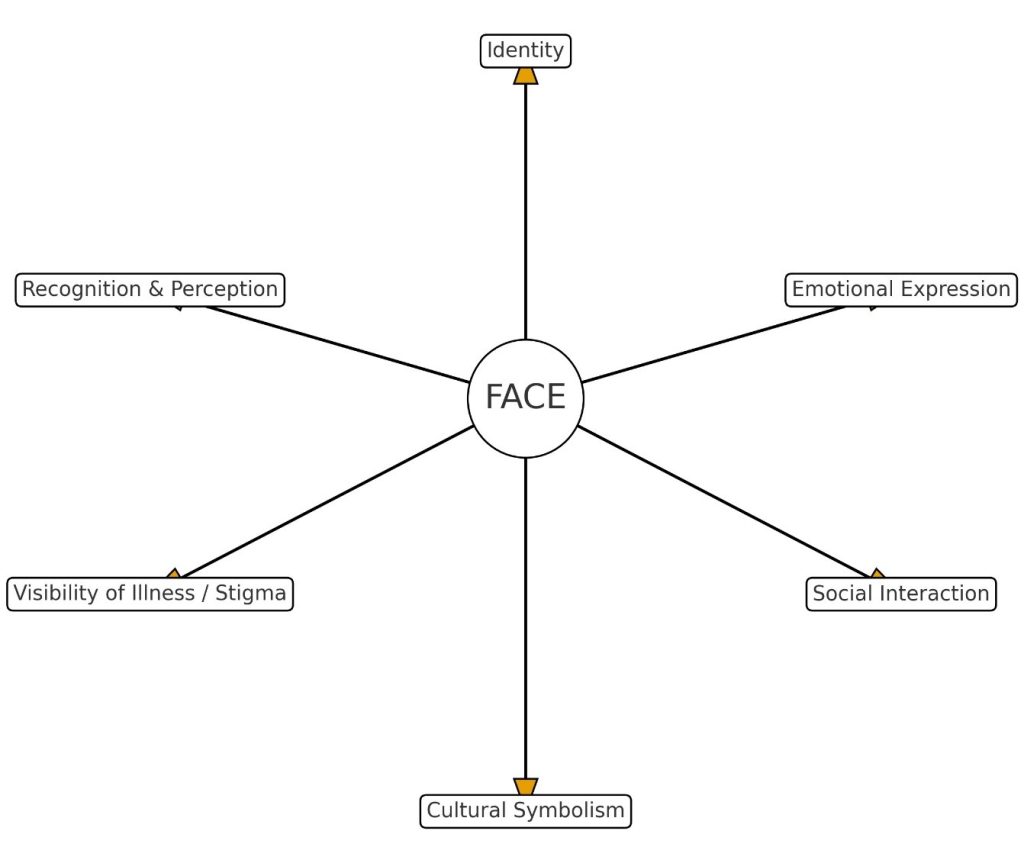

Across cultures, the face has long been regarded as the most significant site of personal expression and social recognition. It conveys emotional states, signals identity, and allows individuals to participate in shared communication without words. Because of this symbolic centrality, changes to facial appearance can hold deeper meaning than alterations elsewhere on the body. In many societies, the face represents a form of personal narrative, carrying traces of experience, status, age, and heritage. When illness disrupts familiar facial features, individuals may feel that a part of their personal story has been interrupted.

Biological and evolutionary research provides insight into why certain facial elements hold particular weight in perception. Specific features—including the eyebrows — assist in rapid recognition, support the interpretation of emotion, and influence assessments of vitality or resilience.[2] These cues function across cultures, suggesting that their importance is not merely aesthetic but connected to fundamental processes of interpersonal understanding. When such cues are altered or lost, individuals must navigate interactions with a face that no longer communicates as they expect. This shift can introduce uncertainty and affect one’s sense of agency in social settings.

The cultural role of the face also extends to expectations of normalcy. Communities often rely on shared visual norms to interpret well-being, and deviations from these norms may be perceived, consciously or unconsciously, as indicators of distress or fragility. As a result, individuals experiencing visible signs of illness may find themselves managing not only their internal emotional response but also the external reactions of those around them. The intersection of biology, perception, and cultural symbolism makes the restoration of facial features a particularly meaningful form of support during recovery.

The Cultural Functions of the Face are depicted below (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Cultural Functions of the Face

ILLNESS, STIGMA, AND IDENTITY RECONSTRUCTION.

Visible signs of illness can influence social interactions in ways that extend beyond an individual’s control. When appearance changes act as unintentional signals of medical history, they reshape how others respond, sometimes eliciting sympathy, discomfort, or avoidance. This dynamic is described in classical sociological theory as the emergence of a “spoiled identity,” in which a person’s public image becomes tied to a condition rather than to their broader sense of self [3]. Such experiences may lead individuals to withdraw socially, limit expression, or feel as though their illness continues to speak for them even after treatment has ended.

Qualitative research on cancer survivorship reveals that many women experience appearance-related changes as among the most significant emotional challenges of treatment [1]. Loss of hair or eyebrows is often described not only as a cosmetic issue but as a visual disruption that alters how survivors relate to their own reflection. Participants in these studies frequently report that these changes make it difficult to recognize themselves, contributing to a sense of fragmentation or discontinuity in personal identity. The transition out of the medical setting does not immediately restore confidence; instead, survivors must navigate a period in which their appearance no longer aligns with their memory of who they were before illness.

These tensions illustrate how visible markers of illness can function as a form of stigma. Individuals may feel exposed or vulnerable when their appearance reveals a private aspect of their history. Everyday encounters—whether with acquaintances, coworkers, or strangers—may be colored by assumptions about health, strength, or recovery. Over time, this can influence emotional stability and shape the trajectory of reintegration into social life. Efforts to restore appearance, therefore, address not only aesthetic concerns but also the broader task of reconstructing a sense of self that is coherent, recognizable, and emotionally sustainable.

Table 1

Emotional Impact Pathway of Post-Illness Appearance Changes

| Stage | Description |

| Appearance Loss | Visible change following illness or treatment. |

| Identity Disruption | Loss of connection with familiar self-image. |

| Social Discomfort | Uncertainty and discomfort in social interactions. |

| Heightened Stigma | Involuntary visibility of illness shapes perception. |

| Emotional Vulnerability | Feelings of fragility, lowered confidence, emotional strain. |

COSMETIC ART AS EMOTIONAL AND CULTURAL HEALING.

Within this landscape, cosmetic reconstruction occupies a unique cultural role. While often perceived as purely aesthetic in commercial contexts, restorative cosmetic practices take on deeper significance for individuals coping with post-illness appearance changes. When used to restore features that have been altered or lost, cosmetic art operates as a bridge between the physical and emotional dimensions of healing. It allows individuals to regain visual continuity with their pre-illness identity, helping them reestablish the sense that their reflection once again corresponds to their internal experience.

Culturally, this process aligns with longstanding traditions in which aesthetic practices serve ceremonial, symbolic, or healing functions. Many societies have used forms of adornment, painting, or reconstruction to mark transitions, recover from loss, or reaffirm identity. In contemporary settings, the restoration of facial features after illness can similarly support emotional recovery by reducing involuntary visibility and restoring a sense of privacy. Survivors often describe the return of familiar features as a moment of regained dignity and control — an important step in detaching the self from the narrative of illness.

Modern restorative techniques make this process more accessible by enabling naturalistic and individualized results. Approaches that prioritize subtlety, accurate facial proportion, and expressive coherence help individuals recover the visual cues that support everyday communication [4]. For survivors who describe difficulty recognizing themselves, such interventions can play a meaningful role in rebuilding confidence. In this sense, cosmetic art becomes part of a broader cultural practice of healing—one that acknowledges the importance of appearance not as vanity but as a foundation of personal identity, social comfort, and psychological resilience.

Table 2

Eyebrows in Human Perception: A Cultural Interpretation Model

| Perceptual Dimension | Cultural / Emotional Role |

| Facial Recognition | Supports immediate identification of the individual; absence disrupts familiarity. |

| Emotional Expressivity | Conveys subtle emotional cues and affects clarity of interpersonal communication. |

| Perceived Vitality | Contributes to impressions of health, resilience, and general wellbeing. |

| Normalcy & Continuity | Signals alignment with socially expected facial features, reducing involuntary visibility of illness. |

| Cultural Aesthetic Norms | Reflects community-specific ideals of balance, symmetry, and personal presentation. |

CASE EXAMPLE: RESTORATIVE AESTHETIC PRACTICE.

The cultural significance of cosmetic reconstruction becomes clearer when examined through examples of contemporary restorative practice. In recent years, specialized forms of cosmetic art have been developed to address the needs of individuals who experience facial changes as a result of medical treatment. These practices do not aim to alter appearance for fashion or trend, but to restore features lost to illness, allowing survivors to reconnect with a sense of normalcy. Naturalistic approaches to eyebrow reconstruction, such as those described in contemporary artistic methods [4], demonstrate how aesthetic skill can be directed toward emotional recovery rather than transformation.

Practitioners engaged in restorative work frequently encounter clients who describe feeling unrecognizable without their eyebrows. For many, the absence of this small facial feature changes the emotional tone of their expression and removes a familiar point of reference in the mirror. Survivors often speak of avoiding photographs, social events, or even eye contact because they feel their face no longer communicates who they are. In this context, the role of the practitioner becomes not merely technical but interpersonal. The process requires sensitivity, patience, and an understanding of how intimately appearance is tied to personal identity.

The Figure 4 visualizes how three cultural and emotional domains intersect in restorative cosmetic art:

Aesthetic Reconstruction — Restoring expressive facial cues and natural appearance.

Emotional Healing — Supporting confidence, dignity, and personal identity after illness.

Cultural Reintegration — Enabling smoother return to social roles and community belonging.

At their intersection — Restored Identity — the core cultural and emotional outcome discussed in the article.

Figure 2. Conceptual Model of Restorative Cosmetic Art

Restorative cosmetic procedures are most effective when the result blends seamlessly with the individual’s natural features, reestablishing expressive cues without drawing attention to the intervention. Techniques that prioritize subtlety, correct proportions, and individualized mapping support this objective. When survivors describe the outcome of such procedures, they often focus not on the aesthetic details themselves but on the emotional effect: the relief of seeing a familiar face, the sense of returning to one’s former self, or the feeling that the illness is no longer written visibly across their features. These responses illustrate how cosmetic art can function as a meaningful component of post-illness healing, offering support that bridges psychological and cultural dimensions of recovery.

CROSS-CULTURAL PERSPECTIVES ON FACIAL RECOVERY.

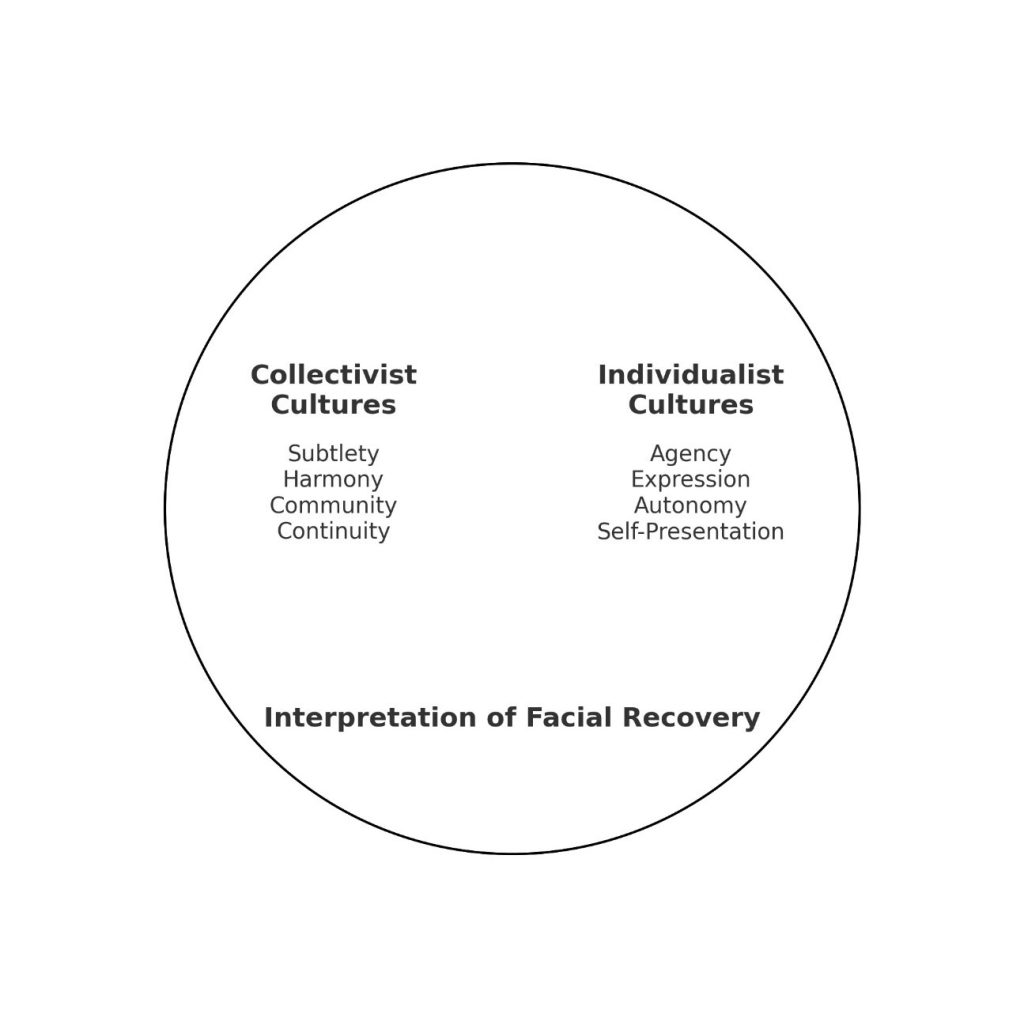

The cultural role of appearance restoration varies across societies, yet common themes emerge surrounding the importance of the face in expressing identity and belonging. In many cultures, the face is perceived as a public canvas through which individuals communicate status, emotion, and personal history. Changes to this canvas—especially when associated with illness—may carry different meanings depending on local norms, but they consistently influence both personal self-understanding and social interaction.

Figure 3. Cultural Forces Shaping Facial Recovery Practices.

In collectivist cultures, where social harmony and shared identity are emphasized, visible signs of illness may lead to heightened feelings of difference or concern about burdening others. In more individualistic cultures, where personal presentation and autonomy are closely tied to self-worth, appearance-related changes may be experienced as a loss of agency or control. Despite these variations, the return of familiar facial features after illness often produces a similar emotional response across cultural contexts: relief, reconnection, and renewed confidence.

The universal role of facial cues in human perception, described in evolutionary research [2], supports the idea that restoring expressive elements can benefit individuals regardless of cultural background. However, the specific aesthetic expectations—such as the preferred density, shape, or prominence of eyebrows—may differ regionally. Restorative practitioners must therefore approach each case with cultural sensitivity, recognizing that “normal” appearance is shaped not only by biological structures but by the aesthetic traditions and social expectations of the community. When restorative methods allow for such individualization, they support more authentic reintegration into cultural and social life.

EMOTIONAL OUTCOMES OF APPEARANCE RESTORATION

The emotional benefits reported by individuals who undergo restorative cosmetic procedures highlight the profound connection between appearance and psychological wellbeing. Survivors of illness often describe the return of familiar facial features as a moment of reorientation—an opportunity to reclaim aspects of identity that felt disrupted or obscured during treatment. Research has shown that changes related to appearance can significantly influence emotional recovery, particularly when those changes involve features central to recognition and expressivity [1]. Restoring eyebrows, for example, can help reduce feelings of vulnerability and diminish the perception that illness remains visible to others. Survivors frequently describe feeling more comfortable engaging in public life after such interventions, as the face no longer cues unwanted attention or sympathy. Naturalistic reconstruction can also help individuals feel more confident in personal interactions, supporting a return to social roles that may have felt challenging during or immediately after treatment.

These emotional outcomes can be understood in relation to sociological perspectives on stigma. When a visible feature associated with illness is effectively restored, individuals often report feeling liberated from the identity imposed on them by their appearance. The intervention becomes not a form of disguise but a restoration of continuity between internal identity and external presentation [3]. In this sense, cosmetic art serves as a culturally embedded form of healing, supporting the reestablishment of dignity, autonomy, and emotional resilience during the transition to post-illness life.

CONCLUSION

The relationship between appearance and emotional wellbeing becomes particularly evident in the period following serious illness, when individuals must navigate not only physical recovery but also shifts in identity, confidence, and social participation. Changes to the face, especially the loss of expressive features such as the eyebrows, may affect how individuals perceive themselves and how they feel perceived by others. These changes can reinforce the sense that illness continues to define one’s public identity, complicating the transition back into everyday life. As research has shown, survivors often identify appearance-related changes as among the most emotionally challenging aspects of treatment, reflecting the broader cultural and symbolic role of the face in shaping personal and social experience [1]. Restorative cosmetic practices provide a way for individuals to regain a sense of familiarity and continuity with their pre-illness selves. Because facial cues play a central role in recognition and emotional communication [2], restoring these elements can help diminish the involuntary visibility of illness and support a smoother reintegration into social environments. When these practices are approached with care, cultural sensitivity, and an emphasis on naturalistic outcomes, they can contribute meaningfully to emotional healing. Survivors frequently describe feeling more confident, more at ease in public settings, and more connected to their personal identity after such interventions. These responses highlight the importance of appearance restoration not merely as an aesthetic preference but as a form of cultural and psychological support.

The sociological framework of stigma further underscores why restorative practices can be so impactful. Visible markers of illness may shape social interactions in ways that reinforce vulnerability or diminish autonomy [3]. By restoring familiar facial features, cosmetic art helps individuals regain control over how they present themselves and how they are perceived. Contemporary methods that emphasize naturalism, proportion, and subtlety allow survivors to reestablish expressive facial cues that align with their internal sense of self [4]. In this way, cosmetic reconstruction becomes part of a broader cultural process of healing, offering not only visual change but renewed confidence and emotional stability.

The cultural and emotional dimensions of appearance restoration suggest that cosmetic art holds a meaningful place within post-illness recovery. It supports individuals in reclaiming identity, managing the social implications of illness, and rebuilding connection with their communities. As awareness of these restorative benefits continues to grow, cosmetic art may increasingly be recognized as a valuable component of holistic healing — one that bridges aesthetic practice with emotional resilience and cultural understanding.

References

1. - Ashing-Giwa, K. T., Padilla, G., Tejero, J., Kraemer, J., Wright, K., Coscarelli, A., Clayton, S., Williams, I., & Hills, D. (2003). Understanding the breast cancer experience of women: A qualitative study of African American, Asian American, Latina, and Caucasian cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology, 12(3), 279–293. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.7502. - Little, A. C., Jones, B. C., & DeBruine, L. M. (2011). Facial attractiveness: Evolutionary based research. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 366(1571), 1638–1659. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0404

3. - Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. https://archive.org/details/stigmanotesonman0000goff

4. Akhmetshina, O. (2025). Authored Method of Permanent Eyebrow Makeup Using the Hair Stroke Technique: Daily Eyebrows. ISBN 978-5-6054348-3-2.