1.Introduction

At present, educational programs at all levels, including primary school, are becoming more complex. Mastering more complex programs requires a higher level of formation of intellectual actions. At the beginning of the 21st century, numerous studies of the problems, methods and ways of teaching thinking were carried out.

1.1 Approaches to stimulate thinking

A study by Adey, P. [2008] characterized thinking development programs for children aged 4–11 years. Dewey, J., & Bento, J. [2009 ] studied the results of a two-year program that activates thinking in elementary school students and noted an improvement in children’s cognitive abilities and social skills, as well as an increase in the professionalism of teachers. De Acedo Lizarraga et al. [2009] showed good opportunities for stimulating intelligence, abstract and deductive reasoning in accordance with the PAEA method.

McGuinness, C. with a group of researchers [2006] analyzed the use of various types of mental tasks to stimulate cognitive skills and identified the most effective ones. Trickey, S., & Topping, K. J. [2004] found that the Philosophy for Children elementary school program had a positive effect on the development of reasoning and argumentation skills in elementary school students.

Lucas, B., & Claxton, G. [2010] studied different types of intelligence (social, practical, strategic, intuitive, etc.) in younger students and identified effective practical tools for teachers in accordance with the noted types of intelligence. Nisbett, R. E et al [2012] have identified the characteristics of the relationship between intelligence and self-regulation, procedural memory and cognitive skills.

The study by Kuhn, D. [2009] shows the importance of children’s understanding of acquired knowledge for assessing learning outcomes. Shayer, M., & Adhami, M. [2007] demonstrated the effectiveness of developing cognitive skills in the study of mathematics. Swartz and McGuinness [2014] explored different possibilities for integrating thinking and academic learning. Puchta, H. and Williams, M. [2011] studied the development of 13 categories of cognitive skills (from simple to complex) in relation to the acquisition of significant practical language skills.

1.2. Brief description of the study

The content of the considered experimental works allows us to note that most researchers use educational material. We believe that it is possible to study the development of thinking and its stimulation on non-educational material. Such material creates favorable conditions for acquiring thinking skills, since, as our works [2004, 2003, 2015] have shown, knowledge of the curriculum does not determine the success of solving search non-standard problems (unlike solving educational problems). Underachieving children perform more confidently in solving such problems than in solving academic problems, because this new experience is not tainted by failure.

The purpose of the study was to study the conditions for the formation of intellectual actions in second-graders related to reasoning, comparison, planning and combination. Hypothesis: 32 lessons in the “Gumption” program are a condition for such formation. In our experiments [2004], it was shown that children, on their own or with little help, can solve simple variants of various types of tasks of the “Gumption” program (here it should be noted that the program under discussion was developed on the basis of our course of developmental activities for students in grades 1–4 “ Intellectika” [ 2002 ].

The study consisted of three stages. At the first stage, two groups of schoolchildren (control — 69, experimental — 73) solved search tasks to determine the degree of development of mental skills. The second stage included 32 lessons in the experimental group according to the » Gumption » program (one lesson per week). At the third stage, the children of both groups again solved the same search tasks.

- Materials and methods

The «Gumption » program is designed to conduct 32 lessons based on 32 types of non-standard tasks with non-educational content: 9 types of plot-logical tasks, 6 types of operational-logical tasks, 8 types of spatial tasks, 9 types of route tasks. Plot-logical tasks contribute to the development of reasoning skills, operational-logical tasks — the ability to compare, spatial tasks — the ability to combine, route tasks — the ability to plan. In each lesson, children solve problems of the same type.

2.1. The content of the program «Gumption».

Lesson 1: route tasks (type 1). Lesson 2: plot-logical tasks (type 1). Lesson 3: spatial problems (type 1). Lesson 4: route tasks (type 2). Lesson 5: operational-logical tasks (type 1). Lesson 6: plot-logical tasks (type 2). Lesson 7: spatial problems (type 2). Lesson 2k 8: route tasks (type 3). Lesson 9: plot-logical tasks (type 3). Lesson 10: operational-logical tasks (type 2). Lesson 11: spatial problems (type 3). Lesson 12: route tasks (type 4). Lesson 13: plot-logical tasks (type 4). Lesson 14: spatial problems (type 4). Lesson 15: operational-logical problems (type 3). Lesson 16: route tasks (type 5). Lesson 17: plot-logical tasks (type 5). Lesson 18: spatial problems (type 5). Lesson 19: route tasks (type 6). Lesson 20: operational-logical tasks (type 4). Lesson 21: plot-logical tasks (type 6). Lesson 22: route tasks (type 7). Lesson 23: spatial problems (type 6). Lesson 24: plot-logical tasks (type 7). Lesson 25: operational-logical tasks (type 5). Lesson 26: route tasks (type 8). Lesson 27: spatial problems (type 7). Lesson 28: plot-logical tasks (type 8). Lesson 29: route tasks (type 9). Lesson 30: operational-logical problems (type 6). Lesson 31: plot-logical tasks (type 9). Lesson 32: spatial problems (type 8).

2.2. Plot-logical tasks.

9 types of plot-logic tasks have the following content.

Type 1, for example: “Dima, Liza and Borya swam across the river. Dima swam faster than Lisa. Lisa swam faster than Borya. Who swam the fastest? »

Type 2, for example: “Words CUTE, CORPS, DOVE in different colors. Blue and pink words have the same first letter, pink and red words have the same second letter. What word is blue?

Type 3, for example: “Edik and Leva are of different ages. In many years, Edik will be a little older than Leva is now. Which one is younger? »

Type 4, for example: “Petya, Yura and Sasha sent letters: two to Ufa, one to Kazan. Petya and Yura, Yura and Sasha sent letters to different cities. Where did Petya send his letter?

Type 5, for example: “Three words were written in blue, red and gray paint: WOOD, CROW, RAINBOW. The blue word is to the left of the red word, and the gray word is to the right of the red word. What color is the word CROW? »

Type 6, for example: “Dima and Katya had cubes with letters. First, Dima made up the word DOM. Then he moved the letters and got the word MOD. Katya first composed the word CAT, and then moved the letters in the same way as Dima. What word did Katya get?”

Type 7, for example: “Three cats lived in the house — gray, white and black: one in the room, one in the hall, one in the attic. In the morning they fed either a black cat or a cat in the attic, in the evening either a cat in the attic or a white cat. Where did the gray cat live?”

Type 8, for example: “Ira, Yulia and Anya received a doll each. One doll was wearing a long-sleeved red dress, another was wearing a short-sleeved red dress, and the third was wearing a long-sleeved green dress. The dresses of Ira and Yulia dolls were of the same color, and Yulia and Anya’s dolls had dresses with the same sleeves. Who had a doll in a red dress with long sleeves?”

Type 9, for example: “Lena and Dasha went to a sports store. Both bought one pair of skis and one pair of skates. Some of the girls liked alpine skiing, some — cross-country skiing, some — roller skates, some — figure skates. Lena left the store without skis. The girl who chose alpine skiing did not buy figure skates. Who bought roller skates?”

At each lesson, children solve 3 variants of tasks of the same type: 1) find the answer, 2) find the question, 3) find part of the conditions.

Option 1 is shown in the examples above.

Option 2, for example: “Dima, Lesha and Borya trained in high jumps. Dima jumped higher than Leni. Dima jumped higher than Borya. Which question can be answered, taking into account the conditions of this problem: a) Who jumped higher than Bori? b) In what style did Borya jump? c) Who jumped below Sloth?”

Option 3, for example: “Gena, Leva and Vova swam across the river. Gena swam faster than Leva. […]. Who swam the fastest?”

What should be added to the conditions of the problem to answer her question: (a) [Vova swam faster than Gena]. (b) [Vova swam as fast as Gena]. (c) [Leva swam faster than Vova].

2.3. Operational-logical tasks.

6 types of tasks for comparing schematic representations of objects have the following contents.

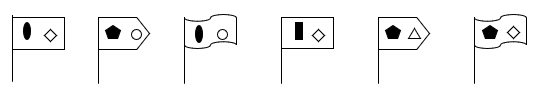

Fig.1. The flags

Fig.1. The flags

Type 1, for example: «Consider flags 2, 3, 6. Which flag is similar in shape to flag 6?»

Type 2, for example: «Flags 1, 3, 5. Which flag has the same feature as flag 5?»

Type 3, for example: «Flags 1, 4, 5. Which flag, 4 or 5, has more of the same features as flag 1?»

Type 4, for example: «Flags 2, 3, 6. Which flag, 2 or 3, is similar in shape to flag 6 but has a dark figure like flag 1?»

Type 5, for example: «Flags 1, 3, 6. Which flag, 1 or 3,A has one identical feature with flag 1 and one identical feature with flag 6?»

Type 6, for example: «Flags 1 — 6». Flags 1 and 6 have the same feature. Which two flags — 2 and 3 or 1 and 4 — have more of the same features than flags 1 and 6?”

At each lesson, children solve 3 options for tasks for tasks of the same type: 1) find the answer, 2) find the question, 3) find part of the conditions.

Option 1 is shown in the examples above.

Option 2, is to find a question, for example: “Flags 2, 3, 6. Which question is appropriate for the answer “Flag 2”: (a) Which flag has a dark figure, such as flag 2? (b) Which flag has a light figure such as flag 3? (c) Which flag has the shape of flag 6?”

Option 3, find part of the conditions, for example: «Flags 3, 6. Which flag has such a light figure as flag 6?» Which third flag is needed to answer this question: (a) flag 2, (b) flag 5, (c) flag 4.

2.4. Spatial tasks.

8 types of spatial problems have the following content.

Type 1, for example: “How can the arrangement of letters | C | | R | change in two moves so that the following arrangement is obtained: | R | C | | ?”

Rule: one move is the movement of any letter to an empty space.

Solution: 1. | C | | R |… | | C | R |; 2. | | C | R |… | R | C | | or | C | | R |… | | C | R |… | R | C | |: on the first move, the letter «C» moves to an empty space, on the second — the letter «R».

Type 2, for example: “How can I arrange the letters | R | R | C | | change in two moves so that the following arrangement of numbers is obtained | 7 | 7 | | 4 | ?

Rule: 1) one move is the movement of any letter to an empty space; 2) the same letters must be placed in the same way as the same numbers.

Solution: | R | R | C | |… | | R | C | R |… | C | R | | R |.

Type 3, for example: “How the arrangement of letters | H | | V | | C | change in two steps to get the location | | H | V | C | | ?”

Rule: one action is the mental movement of any letter to an empty space. Solution: 1. | H | | V | | C | — | | H | V | | C | ; 2. | | H | V | | C | — | | H | V | C | | or | H | | V | | C | — | | H | V | | C | — | | H | V | C | | : the first action moves the letter H to an empty space, the second action moves the letter C to an empty space.

Type 4, for example:: “How the arrangement of letters | K | | K | | F | change in two steps so that the letters are arranged in the same way as the numbers | | 8 | 8 | 4| |?”

Rule: 1) one action is the mental movement of any letter to a free space; 2) the same letters as a result of two actions should be located in the same way as the same numbers.

Solution: | K | | K | | F | — | | K | K | | F | — | | K | K | F | |.

Type 5, for example: “How can you change the arrangement of the letters PMK in two moves to get the arrangement KPM?”

Rule: one move is the simultaneous exchange of two letters.

Solution: PMK … RMB … KPM: first, the letters M and K are reversed, then the letters P and K.

Type 6, for example: «How can you change the arrangement of the letters PPMK in two moves to get the arrangement of the numbers 6855?»

Solution: PMMK… PMMK… PKMM.

Type 7, for example:: “How is the arrangement of letters and numbers | R | G | |7 | change in two steps to get the location | | G | 7 | R | ?”

Solution: | R | G | |7 | — | R | G | 7 | | — | |G| 7 | R | .

Type 8, for example:: “How is the arrangement of letters and numbers | 7 | H | | H | change in two steps to get the location of the signs | # | # | % | | ?”

Solution: | 7 | H | | H | — | | H | 7 | H | — | H | H | 7 | |.

At each lesson, children solve 3 variants of tasks of the same type: 1) find the answer, 2) find the final location, 3) find the initial location.

Option 1 is shown in the examples above.

Option 2, for example: “Which of the following two locations will be: a) | C | | R | or b) | | C | P |, if in the location | R | | C | make two permutations of letters in a free cell?”

Option 3, for example: “What was the location: a) | | C | R | or b) | C | | Р |, if after two moves the arrangement | | R | C | ?”

- 5. Route tasks.

Below is the content of 9 types of tasks related to the movement of imaginary characters according to certain rules.

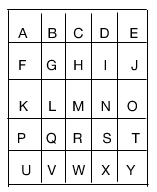

Fig.2. Playing field 1

Type 1, e.g.: ““What two steps did the chicken take to get from K to R?”

Rule: 1) “Chicken”, an imaginary character, moves through the letters in the “cells” of the “square”; 2) the characteristics of its movements are: (a) it steps directly, i.e., into a neighboring cell vertically (e.g.: from M to H or to R) or horizontally (e.g.: from M to N or L); (b) it steps obliquely, i.e., diagonally,(e.g.: from M to G or I or S or Q); 3) duck can not make two identical steps (two direct steps or two oblique steps) in succession. Solution: K…L…R.

Type 2, e.g.: “What two jumps did the take dog to get from K to E?”

Rule: 1) “Dog”, an imaginary character, moves through the letters in the “cells” of the “square”; 2) the characteristics of its movements are: (a) it jumps directly, i.e., through the letter vertically (e.g.: from M to C or W) or horizontally (e.g.: from M to K or O); (b) it jumps obliquely, i.e., diagonally, e.g.: from M to E or A or U or Y; 3) hare can not make two identical jumps (two direct jumps or two oblique jumps) in succession. Solution: K…M…E.

Type 3, e.g.: “What two jumps did the cat take to get from K to S?”

Rule: 1) “Cat”, an imaginary character, moves through the letters in the cells of the square; 2) the characteristics of its movements are as follows: it jumps through the letter (e.g.: from M to F or B or D or J or T or X or V or P). Solution: K…V…S.

Type 4, e.g.: “What two moves do the chicken k (directly) and the dog (obliquely) need to make in order to get from G to T?” Solution: G…H…T.

Type 5, e.g.: “What two moves do the chicken (obliquely) and the dog (directly) need to make in order to get from H to S?” Solution: H…G…V.

Type 6, e.g.: “What two moves do the chicken (directly) and the cat need to make in order to get from B to J?” Solution: B…C…J.

Type 7, e.g.: “What two moves do the chicken (obliquely) and the cat need to make in order to get from D to Q?” Solution: D…H…Q.

Type 8, e.g.: “What two moves do the dog (directly) and the cat need to make in order to get from R to E?” Solution: R…H…E.

Type 9, e.g.: “What two moves do the dog (obliquely) and the cat need to make in order to get from G to V?” Solution: G…S…V.

At each lesson, children solve 3 variants of tasks of the same type: 1) find the answer, 2) find the final cell of displacements, 3) find the initial cell of displacements.

Option 1 is shown in the examples above.

Option 2, for example: “Which cell did the duck get two steps from C: cell W or cell O?”

Option 3, for example: “From which cell did the duck get to Y in two steps: from cell X or K?”

2.6. Features of developing activities.

The lesson on the program «Gumption» consists of three parts. In the first part (about 15 minutes), the teacher, together with the students, analyzes ways to solve a typical problem. Children need to understand what to look for in this type of problem and how it can be achieved. To do this, they are given the tools to analyze problems and ways to manage the search for solutions and control their actions.

In the second part (about 30 minutes), children independently solve 12 to 15 problems, applying the knowledge gained in the first part. In the third part (about 15 minutes), the teacher, together with the students, checks the solved problems and considers incorrect solutions, once again demonstrating the methods of problem analysis and ways to control mental activity.

- Results

3.1. Diagnostics of thinking skills.

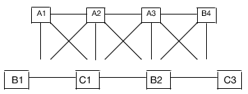

Before and after 32 classes, group diagnostics were carried out on the basis of search tasks, in which it was necessary to find the movement of the «Postman» between the «houses» on the playing field (fig.3):

Fig.3. Playing field 2

The «Postman» moves according to the following rule: if two neighboring «houses» have the same «resident» — a letter or number (for example, houses A2 and B2 or A2 and A3), then you can walk along the path between such houses; if — the «houses» do not have the same «resident» (for example, A2 and B3), then — you can’t go.

For example, such a problem: “What two moves does the Postman need to make to get from A2 to C3 (A2…?… C3)?” Solution: A2…A3…C3.

After explaining the Postman’s movement rule, it was proposed to solve six problems:

(1)A1…? …B2;

(2) IN 1…? … A2;

(3) B2…? …? …C3;

(4) A3…? …? …B4;

(5) C1…? …? …? …B4;

(6) B4…? …? …? …B1.

3.2. The main results of the study.

Quantitative characteristics of the success of solving diagnostic problems by second-graders are presented in the table.

Table.

Children of the control and experimental groups who solved six problems in September and May (in %)

| Groups | September | May |

| Control | 23,2 | 34,8 |

| Experimental | 20,5** | 57,5** |

| Note: **p<0.01 | ||

According to the data presented in the table, the level of development of mental skills in May increased (compared to September) in both groups: by 11.6% in the control group, by 37.0% in the experimental group. In September, the difference was minimal — 2.7%, and in May it became statistically significant — 22.7% (at p <0.01). Thus, the conducted study confirmed the initial hypothesis that the “Gumption” program contributes to the formation of intellectual actions in second-graders.

- Discussion

4.1. Experimental conditions.

The results obtained in the study are explained by the peculiarities of the content of the “Gumption” program: the non-educational content of tasks, their search nature, the variety of their types (plot-logical tasks, operational-logical, spatial, route), structural differences and differences in tasks: find an answer, find a question , find part of the condition.

The specific characteristics of the implementation of the “Gumption” program are also important: 32 hour sessions held weekly for nine months. Each lesson consists of three parts — preliminary discussion, independent problem solving, final discussion.

The subjects were ordinary students in ordinary classes of two ordinary schools. The control group consisted of two classes in one school and one class in another school, while the experimental group consisted of one class in the first school and two classes in the second school.

Classes were conducted by ordinary elementary school teachers.

4.2. Scientific significance of the study As a result of the experiments, new knowledge was obtained about the conditions for the formation of mental skills, expanding and clarifying the ideas of developmental psychology about the possibilities of intellectual development of younger students.

4.3. The influence of developmental activities.

Observations of the actions of students testified to changes in their behavior: they were no longer afraid of mistakes, offering their own solutions. Children who failed to solve all six diagnostic tasks in September initially showed increased anxiety, but subsequently gained more confidence and became more active in discussions.

When solving problems independently, these children were supported for eight lessons: the teacher reminded them of the rules for solving specific types of problems, indicated the elements of the conditions that must be taken into account, and helped them understand errors in incorrect solutions.

The students who solved all the problems in September were also supported: the teacher offered to compose problems similar to those solved. As our studies show [2003], [2016], such tasks contribute to the development of mental skills and creative thinking.

In conversations with teachers, it was noted that they made certain changes in their work. In particular, they began to offer more problems with incomplete conditions or missing questions, and also gave children problems that required verification of the finished solution. Speaking about changes in the behavior of students in the lessons according to the school curriculum, teachers noted the increased activity of children in class discussions, emphasizing the fact that children began to reason more consistently when solving mathematical problems and give more examples when studying grammar rules).

4.4. Research limitations.

In September, on average, 21.8% of students solved six problems in both groups. With a different composition of the group, where the results were, for example, 15.0% or 10.0%, the effectiveness of developmental classes could be lower.

The pedagogical experience of the teachers who conducted the classes was, on average, 15-20 years, whereas if it had been 3-5 years, the development of the children in the experimental group would have been less effective.

4.5. Goals of further research

Conduct a similar study with third-graders to more fully and accurately assess the impact of the «Gumption» program on the development of thinking skills in children of primary school age.

Determine the optimal composition of the search tasks for each age level of the «Gumption» program and check the effectiveness of other types of tasks.

To study new options for the frequency of developmental classes per month, as well as the duration of one lesson and its three parts. It is important to investigate the impact on the effectiveness of developmental activities of the number of children in the class, as well as their composition based on the results of the initial diagnosis.

Create a comprehensive program for the formation of intellectual activity among younger schoolchildren, in which the “Ingenuity” program would serve as propaedeutics in the course of the development of critical and creative thinking [2016].

- Conclusion

The study demonstrated the effectiveness of the development of thinking skills in second-graders in group activities, when on a regular basis (once a week) for nine months (from September to May) various types of search tasks of non-educational content included in the “Gumption” program were solved.

References

1. Adey, P., (Ed.), (2008). Let’s think handbook: A guide to cognitive acceleration in the primary school. London: GL Assessment.2. De Acedo Lizarraga, M., De Acedo Baquedano, M., Goicoa Mangado, T., & Cardelle-Elawar, M. (2009). Enhancement of thinking skills: Effects of two intervention methods. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 4(1), 30-43.

3. Dewey, J., & Bento, J. (2009). Activating children's thinking skills (ACTS): The effects of an infusi4on approach to teaching thinking in primary schools. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 79(2), 329-351.

4. Kuhn, D. (2009). The importance of learning about knowing: Creating a foundation for development of intellectual values. Child Development Perspectives, 3(2), 112-117.

6. Lucas, B., & Claxton, G. (2010). New kinds of smart: How the science of learnable intelligence is changing education. Maidenhead, UK: McGraw-Hill International.

7. McGuinness, C., Sheehy, N., Curry, C., Eakin, A., Evans, C., & Forbes, P. (2006). Building thinking skills in thinking classrooms. ACTS (Activating Children’s Thinking Skills) in Northern Ireland. London, UK: ESRC’s Teaching and Learning Research Programme, Research Briefing No 18.

8. Nisbett, R. E., Aronson, J., Blair, C., Dickens, W., Flynn, J., Halpern, D. F., et al. (2012). Intelligence: New findings and theoretical developments. American Psychologist, 67(2), 130-159.

9. Puchta, H. and Williams, M. (2011). Teaching Young Learners to Think. Innsbruck and Cambridge: Helbling Languages and Cambridge University Press.

10. Shayer, M., & Adhami, M. (2007). Fostering cognitive development through the context of mathematics: Results of the CAME project. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 64(3), 265-291.

11. Swartz, R. and McGuinness, C. (2014). Developing and Assessing Thinking Skills. Project Final Report Part 1 February 2014 with all appendices.

http://www.ibo.org/globalassets/publications/ib-research/continuum/student-thinking-skills-report-part-1.pdf

12. Trickey, S., & Topping, K. J. (2004). Philosophy for children: A systematic review. Research Papers in Education, 19(3), 365-380.

13. Zak A. (2002).IntellectIKA. М.: Intellect-Centr [in Russian].

14 Zak A. (2003). Characteristics of individual differences in the thinking of younger students. Sankt-Peterburg: Piramida [in Russian].

15. Zak A. (2004). Thinking of the younger school student. Sankt-Peterburg: Sodeystvie [in Russian].

16. Zak A. (2015). Improvement of cognitive and regulatory actions in elementary school. Sankt-Peterburg: Proekcia [in Russian].

17. Zak A. (2016). Development of author’s thinking in younger schoolchildren. Moscow: Biblio-Globus [in Russian].