- INTRODUCTION

By selecting and placing the right people in the right jobs, migration will stabilize and organizational efficiency will increase. In our country, citizens will have secure jobs and organizations will work productively, contributing significantly to economic growth and development. If the number of applicants for a given organization is high, on the one hand, it is a testament to its high reputation in the market, and on the other hand, it is a testament to the fact that it is pursuing a sound human resources policy.

The ability of global companies to adopt new technologies is hampered by a skills shortage. The skills shortage and incompetence in the labor market are hindering the attraction of the right talent and the adoption of new technologies. It is the responsibility of universities to prepare competent and mature specialists who can respond to environmental changes and meet the demands of a knowledge society.

Therefore, it is considered essential to study the requirements of the Mongolian labor market, or human resource selection, based on job advertisement information and identify the most sought-after skills in order to develop policies and programs for training specialists at universities.

- RESEARCH ON SKILLS REQUIRED FOR HUMAN RESOURCES SELECTION

McClelland (1973), an American psychologist, popularized the concept of competencies as a means of determining the value of employees’ abilities. Boyatzis (1982) and Spencer and Spencer (1993) refined the concept and proposed a theory of competencies for use in business and educational research. «Competencies» refer to the observable elements (such as knowledge and skills) and underlying characteristics (such as attitudes, personality, and motivation) that lead to high job performance (Boyatzis, 1982) (Fleming et al., 2009; Le Deiste and Winterton, 2005; McLagan, 1997).

A list of competencies can be developed by analysing the work situation in the workplace (Campion et al., 2011). The list should include specific knowledge, skills and attitudes that are required to perform the job effectively (Miller et al., 2012). In a survey of employers in Scotland, “trustworthiness”, “reliability”, “emotional”, “communication skills” and “willingness to learn” were considered the most important transferable skills when hiring graduates (McMurray et al., 2016). From a workplace perspective, Deacono et al. (2014) reported that employers were most satisfied with graduates’ “responsibility”, “planning and organising activities” and “agility and effective time management”.

Ryan et al. (2012) found that content analysis of interview data on skills predicts business profitability, with skills such as “team leadership”, “achievement orientation”, “development of others”, and “influence on others” being the most important predictors of business profitability. These studies suggest that there is a clear gap between the skills that graduates possess and the skills that lead to business success. Based on data collected from job advertisements in newspaper classifieds, Dunbar et al. (2016) found that employers focus more on soft skills and discuss technical skills more than on soft skills.

Further supporting this hypothesis, an online survey conducted in the UK found that HR professionals were highly impressed with the technical skills of graduates, but expressed concerns about their personal skills and attributes (Poon, 2014). A survey of the Romanian labour market found that employers place a higher value on transversal competencies (Deaconu et al., 2014). Jackson and Chapman (2012) surveyed 143 organisations and found that students were confident and competent in technical aspects, but significantly lacking in business skills.

Each year, the World Economic Forum publishes a report called «Future of Jobs,» which compiles research findings from member organizations and their executives. The report highlights labor market trends, employer expectations, and workforce skill shifts, and highlights the most interesting findings.

This time, Signature magazine presents the most interesting part of the report, published last month, which lists the skills that will be most valued in the labor market in 2025. It emphasizes that in just five years, 50 percent of professionals actively working in the labor market will need to upgrade their skills and change them in line with the characteristics of the market. This is largely due to the changing nature of our work tools, environments, and tasks, driven by technological advancements and the industrial revolution. Critical thinking and problem-solving have topped the list of most in-demand skills since the report was first released. Critical thinking and problem-solving will continue to be the top skills in 2025. In addition, new personal management skills such as active learning, resilience, and stress management have been added. This shows that employers are starting to recognize the importance of mental health in today’s world of work-life balance. As a younger generation with new approaches and new mindsets enters the workplace, continuous learning and acquiring new skills is becoming more important. On the other hand, due to the digital transformation, the ability to use and adapt to technology, as well as mastering programming and technology languages, is becoming an advantage.

The value of decision-making and creative thinking, which have been considered important in traditional business environments, is still relevant. The acquisition of new skills depends on many factors and takes a lot of time. The report highlights the role and involvement of business leaders in shortening this time and reducing the burden and stress on employees. They also mentioned how they can support their employees by providing them with opportunities to develop themselves and by providing them with necessary training and programs. The most notable of these was the time it takes to master new skills. It takes one to two months for a person to learn any type of cultural, sales, or marketing-related skill. The theory behind these areas is that there are many well-developed, practice-based tools available today. However, it takes three to four months to develop skills related to product development and data. These are considered «average» in terms of time spent, as they involve working on some things yourself and building on specific examples and experiences. The skills that take the longest, at more than five months, are programming and computer skills. In short, learning these skills requires a lot of effort from the individual, as the technical tools and theoretical understanding are constantly being updated.

This is confirmed by the findings of a survey of more than 3,000 C-suite executives in seven countries: Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The study looked at the skills shift in five industries in more detail. The analysis highlighted many similarities in the changing patterns of skill requirements. For example, while social and emotional skills will be in demand across all five industries, the need for core cognitive skills has remained stable in healthcare and declined slightly in banking, manufacturing, and retail.

Table 1

Skills transfer

| Banking & Insurance | Financial services have been at the forefront of digital adoption. Banking and insurance are expected to see a dramatic shift in skill demands through 2030. The financial services sector holds many opportunities for the use of artificial intelligence, particularly in risk prediction and personalizing product marketing to consumers. |

| Energy & Mining | Automation and artificial intelligence are enabling companies to exploit new resources and increase the efficiency of extraction and production. Demand for data analysis and technology jobs is expected to grow. Along with basic cognitive skills, demand for physical and manual skills is expected to decrease, while demand for higher-level cognitive, social, emotional, and technological skills is expected to increase. |

| Healthcare | Automation and artificial intelligence will transform the relationship between patients and healthcare professionals. The automation of administrative and clerical tasks will continue to increase the demand for care providers such as nurses, while office assistants will decline.

Healthcare is the only sector where the need for physical and manual skills will increase in the years to 2030. This change will increase the demand for nursing, physical therapy, and other skilled nursing jobs. |

| Manufacturing | The overall need for physical and manual skills in this sector is halving. As office support functions are automated, the need for basic cognitive skills is also decreasing. The number of professionals such as sales representatives, engineers, managers, and executives is expected to increase.

This will lead to an increase in social and emotional skills, especially communication, negotiation, leadership, management, and adaptability. As the need for technological skills increases, both in advanced IT skills and basic digital skills, the number of technology professionals will increase. The demand for higher cognitive skills will increase due to the need for more creativity and complex information. |

| Retail | Intelligent automation and artificial intelligence will transform retailers’ revenue and profit margins, as self-checkout machines replace cash registers, robots reorganize shelves, and machine learning improves the ability to predict customer demand.

The proportion of predictable manual tasks, such as driving, packing, and stacking, will decline significantly. The remaining jobs will likely focus on customer service, management, and technology operations and maintenance. Demand for physical and manual skills will decline, while demand for interpersonal skills, creativity, and empathy will increase. |

III. RESEARCH SECTION

A total of 481 organizations studied job advertisements in 12 sectors. The study analyzed 587 job advertisements from 481 organizations in 12 sectors: wholesale and retail trade, processing industry, transportation and bonded warehouses, information and communication, construction, mining and quarrying, hotels and catering, finance and insurance activities, health, human resources, education, and others. To determine the frequency of the total number of advertised positions, 241 types of positions were ranked from 1 to 25.

Table 2.

Number of organizations covered in the survey and number of job announcements by specific sector.

| № | Sector | Number of Organizations | Total Number of Job Advertisements |

| 1 | Education | 11 | 67 |

| 2 | Human Resources | 42 | 60 |

| 3 | Wholesale and Retail | 57 | 50 |

| 4 | Manufacturing | 44 | 50 |

| 5 | Transport, Customs, and Warehousing | 37 | 50 |

| 6 | Information and communication | 36 | 50 |

| 7 | Construction | 42 | 50 |

| 8 | Mining and extraction | 37 | 50 |

| 9 | Hotels and catering | 47 | 50 |

| 10 | Financial and insurance activities | 44 | 45 |

| 11 | Healthcare | 40 | 15 |

| 12 | Other | 44 | 50 |

| Total | 481 | ||

The human resources selection requirements of the organizations surveyed were examined. The study concluded that the most frequently mentioned skills in job advertisements are communication skills and computer skills. These are the most important skills for employees. In addition, teamwork and foreign language skills are essential skills. The 5 most frequently mentioned skills are shown in the figure.

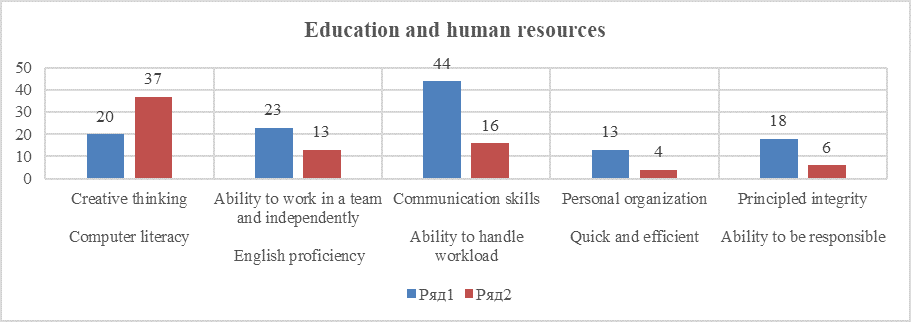

Figure 2. Skills in the education and human resources sector

In the education and human resources sector, 44 out of 60 employers prioritized communication skills and a positive attitude, 37 computer skills, 23 teamwork and independent work, and 20 creativity.

The following skills were considered essential: 18 organizational and planning skills, 16 document management skills, 13 personal organization skills, 13 English language skills, 6 leadership skills, 6 teaching skills, and 4 processing skills.

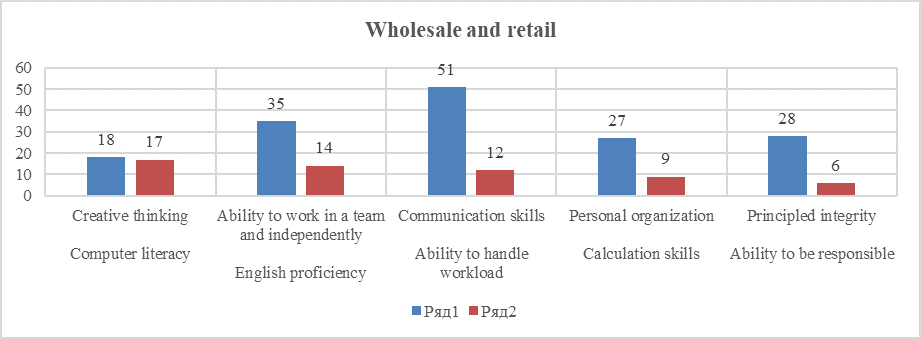

Figure 3. Skills in the wholesale and retail sectors

In the wholesale and retail sectors, 51 out of 67 employers considered communication skills and a positive attitude, 35 teamwork and independent work skills, 28 integrity and ethics, and 27 personal organization as important criteria. 18 considered creative thinking, 17 computer application knowledge, 14 English language knowledge, 12 communication skills, 9 numeracy, and 6 responsibility as necessary skills.

Figure 4. Processing industry /food, industry, other/sector skills

In the processing industry (food, industry, other) sector, 35 out of 60 employers considered communication skills and a positive attitude, 34 teamwork and independent work skills, 25 the ability to be principled, honest, and ethical, 18 personal organization, 20 creative thinking, 10 computer application knowledge, 7 English language knowledge, 5 the ability to handle a workload, 4 the ability to be quick-witted, and 10 responsibility as necessary skills.

Figure 5. Skills in the information and communication sector

In the information and communications sector, 36 out of 50 employers considered the following skills necessary: the ability to use computer programs, 30 a positive attitude towards communication culture, 28 the ability to work in a team and independently, 25 creative and logical thinking, 20 foreign language skills, 17 knowledge of information and communications and network technology, 16 principled and fair morals, 15 good personal organization, 7 the ability to analyze problems and make rational decisions, and 5 an artistic sense for color design.

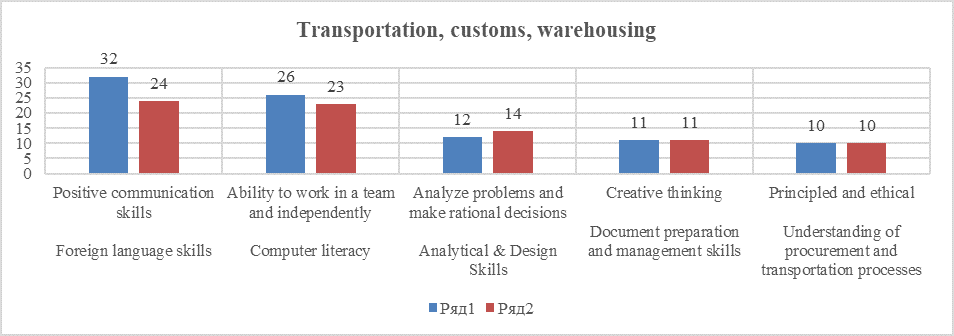

Figure 6. Skills of transport, warehouse and customs workers

In the transportation, customs, and warehousing sectors, 32 out of 50 employers considered foreign language skills, 24 positive communication skills, 23 computer skills, 23 teamwork and independent work, 14 problem-solving and decision-making skills, 12 computational skills, 11 document management skills, and 10 knowledge of the procurement and transportation sectors as professional skills. In business skills, 11 considered creative thinking and 10 considered ethical and moral skills as necessary skills.

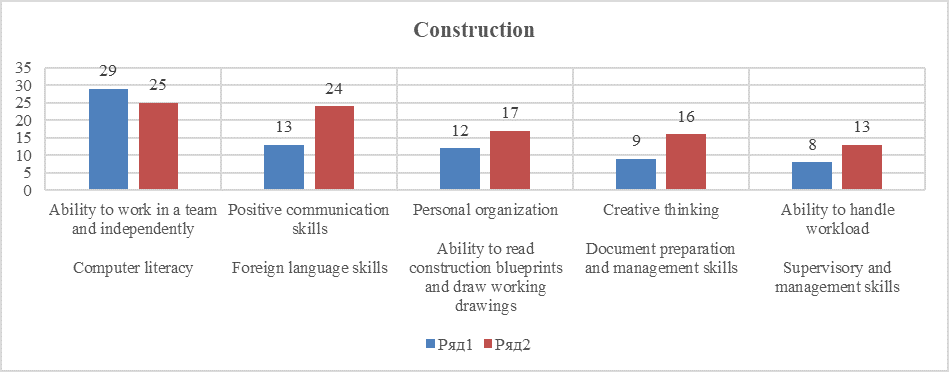

Figure 7. Skills in the construction industry

In the construction industry, 29 out of 50 employers required professional skills such as computer skills, 13 foreign language skills, 12 reading and drawing construction drawings, 9 document processing skills, and 8 control and management skills. In business skills, 25 required the ability to work in a team and independently, 24 positive communication skills, 17 good personal organization, 16 creative thinking, and 13 the ability to handle workload.

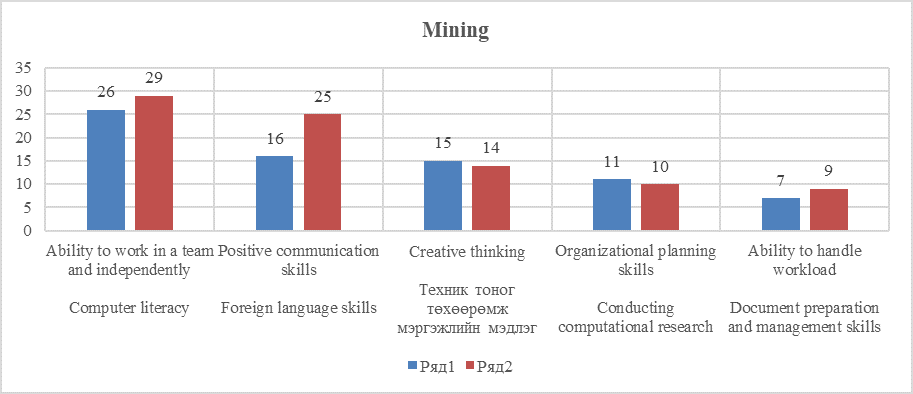

Figure 8. Skills in the mining sector

In the mining industry, 29 out of 50 employers considered the ability to work in a team and independently, 26 the ability to work with computer programs, 25 communication skills and a positive attitude, while 16 considered foreign language skills, 15 technical equipment skills, 14 creative thinking, 11 the ability to conduct research, 10 the ability to organize and plan, 9 the ability to handle a workload, and 7 the ability to process and maintain documents.

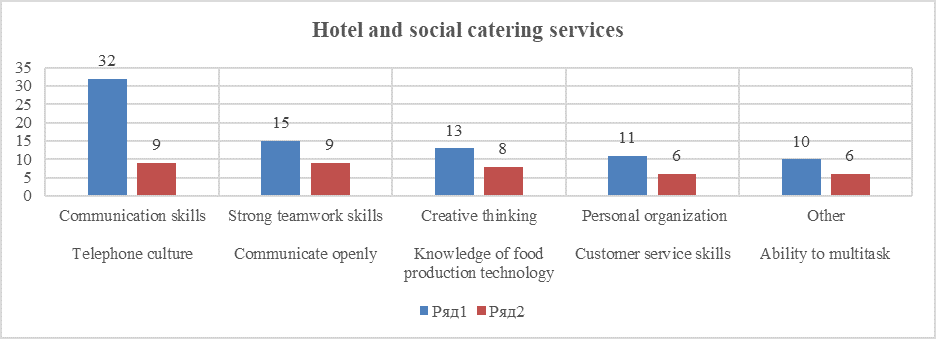

Figure 9. Skills in the hotel and catering industry

In the hotel and catering industry, 32 out of 50 employers considered communication skills, 15 teamwork skills, 13 creativity and initiative, while 11 considered personal organization, 9 telephone skills, 9 open communication, 8 knowledge of food production technology, 6 customer service skills, and 6 the ability to multitask.

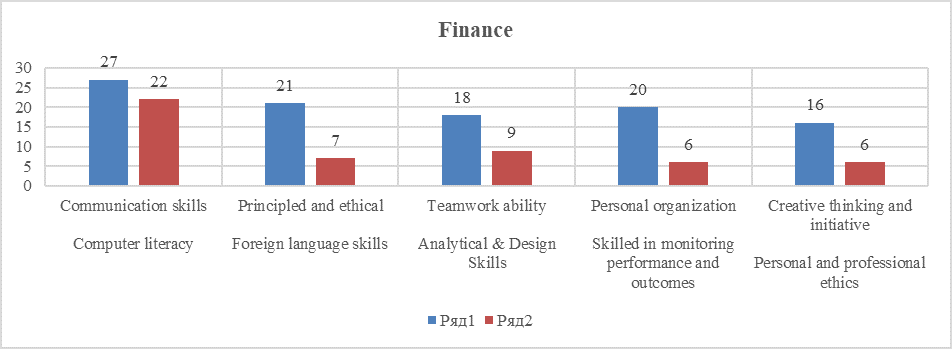

Figure 10. Financial sector skills

In the financial and insurance sector, 27 out of 50 employers considered communication skills, 22 computer skills, 21 integrity, and 20 personal organizational skills as important, while 18 considered teamwork skills, 16 creative thinking and initiative, 9 calculation skills, 7 foreign language skills, 6 results monitoring and analysis skills, and 6 personal and professional ethics as necessary skills.

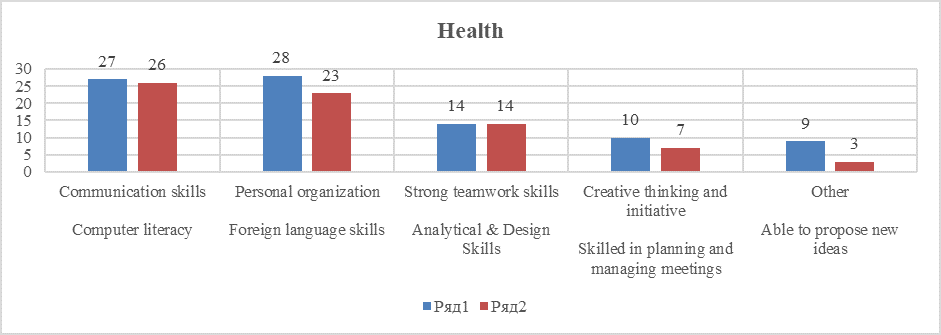

Figure 11. Skills in the health sector

In the healthcare sector, 28 out of 50 employers considered teamwork skills, 27 communication skills, 26 computer skills, 23 foreign language skills, and 14 medical license as necessary skills. 14 considered creativity and initiative, 10 considered personal organization, 9 considered the ability to handle workload, 7 considered the ability to provide service, and 3 considered the ability to comply with medical service standards.

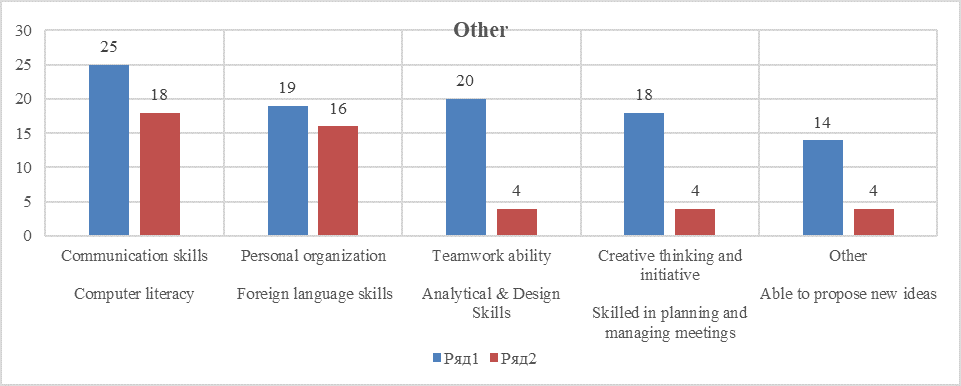

Figure 12. Skills in other sectors

In the Other sector, 25 out of 50 employers considered communication skills, 20 teamwork skills, 19 personal organization, 18 creativity and initiative, and 18 computer skills as important skills, while 16 considered foreign language skills, 4 calculating and designing skills, 4 coordinating and planning official meetings, and 4 considering the ability to come up with new ideas as necessary skills.

Table 2.

Results of the skills

| Professional skills /hard skills/ | Ranking | Personal skills /soft skills/ | Ranking | ||

| Skills | Job posting frequency | Skills | Job posting frequency | ||

| Computer programming skills | 260 | II | communication culture, positive attitude | 308 | I |

| English language skills | 194 | IV | teamwork and independent work skills | 240 | III |

| Document preparation and management skills | 83 | VII | personal organization | 125 | V |

| Calculative skills | 82 | VIII | principled honesty and ethics | 92 | VI |

| innovative logical thinking | 33 | IX | |||

In summary, the analysis of the human resource recruitment requirements or job advertisements of 567 employers in 11 sectors was conducted. It can be concluded that the most important skills are personal skills /soft skills/. This means that communication culture and a positive attitude towards work in the workplace have a direct impact on organizational culture and customer satisfaction. However, it is proven that teamwork and independent work skills have a direct impact on work productivity.

CONCLUSION

As a result of the study of human resource selection requirements based on job advertisement data, the skills needed in the labor market or those that are important for each sector have been identified.

The survey concluded that the need for personal skills was high. For example, among personal skills, communication skills, positive attitude, teamwork skills, and personal organization were considered to be important. However, among professional skills, the need for computer skills, English language skills, and document preparation and management skills were considered to be more important. Today, universities need to update their curricula and methods to meet the needs and expectations of employers and meet the demands of the times.

For employers, there is an opportunity to fill skill gaps by reskilling or upskilling their current workforce based on an assessment of their skills. However, it is not enough for employees to attend these trainings. For employees, there is an opportunity to improve their skills and qualifications in the workplace with the support of the employer. It is believed that there is an opportunity to work with university teachers to develop workplace training programs to fill skill gaps.

References

References1. Aikin, M.W., J.S. Martin, and J.G.P. Paolillo, 1994, Requisite skills of business school graduates: Perceptions of senior corporate executives, Journal of Education for Business, 69(3), 159-162.

2. Baty, P. (2007) Concern at rise in top degrees. Times Higher Education Supplement 12 January 2007 p2

3. Bennett, N., E. Dunne, and C. Carre, 2000, Skills Development in Higher Education and Employment Buckingham: SRHE & Open University Press.

4. Cranmer, S. (2006) Enhancing graduate employability: best intentions and mixed outcomes. Studies in Higher Education, 31 (2), 169–184

5. Denholm, J. (2004) Considering the UK Honours degree classification method, a report for the QAA/SHEFC Quality Enhancement Theme Group on Assessment Edinburgh: Critical Thinking

6. Gabric, D., and K. McFadden, 2000, Student and employer perceptions of desirable entry-level operations management skills, Mid-American Journal of Business, 16, 51-59.

7. Gati, I., 1998, Using career-related aspects to elicit preferences and characterize occupations for a better person-environment fit, Journal of Vocational behaviour, 52(3), 343-356.

8. Haigh, M.J., and M.P. Kilmartin, 1999, Student perceptions of the development of personal transferable skills, Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 23(2), 195–206.

9. Morley, L. and Aynsley, S. (2007) Employers, quality and standards in higher education: shared values and vocabularies or elitism and inequalities? Higher Education Quarterly, 61 (3), 229–249